CAMAGÜEY.- When the tower of the Iglesia Mayor collapsed around ten o'clock at night on February 24, 1777, crushing part of the building, the first thing that Mayor Don Jacinto Agramonte did was order an investigation, since the work had barely been completed a month ago. It was inaugurated with religious festivities and blessings. Later, with the rubble, he filled in the neighboring lot that at times served as an exercise area for the Villa's garrison.

In fact, to date, this space already existed that Colonel Diego Antonio de Bringas, head of the troop, had taken as the Plaza de Armas in a population, then, of just over 13,000 inhabitants.

Don Agramonte was also concerned about the nearby cemetery, located at the back of the church and bordering the Square. In short, the new tower was not ready until 1797 and nothing is known about the results of that investigation. The fosal remained in that place until in 1813, the cemetery was inaugurated next to the church of Cristo del Buen Viaje.

Our Plaza de Armas was from the 18th century Plaza de Marte and when in 1812 the Spanish monarchy became entangled in internal political disagreements approving changes in its royal laws, with a beating drum and side reading, it was baptized as Plaza de la Constitución. Since December 8, he made an appearance at Villa El Espejo, the first printed newspaper published in Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe thanks to the diligence of the Havana typographer Mariano Seguí de los OIivos, who with a certain constitutional “benevolence” gave them to criticize the hygiene and the neglect of the place and the negligence of councilors and other officials.

The momentum did not last long, because two years later the Constitution was abolished in Spain, freedoms were repressed and the agora was then Plaza de la Iglesia Mayor. El Espejo was accused of denigrating the lieutenant governor and as he wrote again about the same and the abandonment of the streets, he was threatened for "propagating revolutionary ideas and disloyalty." Seguí sold the printing press and returned to Havana.

When in 1820 the constitutionalists took back command in the Courts of the kingdom, it was called Parque de la Constitución with parties for three days, the inauguration of the first public sale and the carrying out of some works to improve the area. A commemorative obelisk was erected to the Magna Carta and the healthy custom of whipping was abolished as a correctional punishment imposed by the courts on the whites, (blacks and slaves continued in the enjoyment of the old laws) , which was an attractive spectacle in the central esplanade. There was always a gallows in operation in public view for what you must imagine.

With this or without it in Spain the Constitution was revoked again in 1824 and started again. In our city, fights broke out between royalists and constitutionalists in the Central Plaza with the intervention of spearmen, and there were a good number of wounded and detained.

On March 16, 1826, the patriots Francisco Agüero y Velasco and Andrés Manuel Leocadio Sánchez, the first people from Camagüey who fell in the long martyrology for the independence of Cuba, were executed in the Plaza Mayor until in 1839 when the works of embellished with palms, Indian laurels and a central fountain, but without water, it was renamed Plaza del Recreo and from 1845 on to the Queen, in honor of María Cristina de Borbón-Dos Sicilias, wife of King Fernando VII and regent of the future monarch Elizabeth II.

Of course, whipping and hanging were not compatible with the august lady, so these instruments of distraction moved to the Plaza del Cristo. By the 1890s, they became habitual every Sunday morning after the Mass in the Cathedral Church, the marching bands of the Zaragoza and Cádiz infantry battalions.

El Lugareño and the press of the time were the architects of the modernization that from the middle of the 19th century brought it closer to its current image. Finally, in December 1899, the City Council agreed to distinguish this attractive public space as Parque Agramonte.

On May 8, 1910, the leadership of the Popular Society of Santa Cecilia sponsored the idea of a statue to El Mayor. They selected from among many proposals the work of the Italian sculptor Salvador Boemi, as the most beautiful and economical, with the recommendation that two lions located at the base of the pedestal be eliminated from the original project and replaced by war mortars. Incidentally, the mortars were lost on the journey from Italy to Cuba, and never appeared.

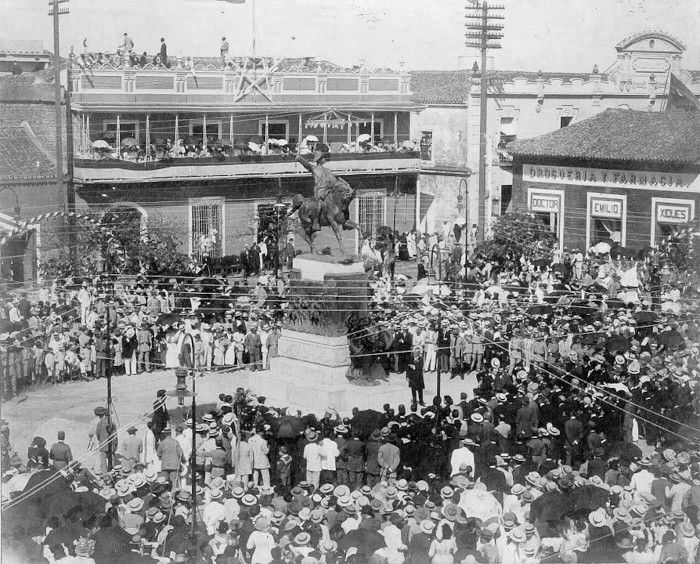

The press of the time reported the inauguration of the monument in a brief chronicle: “At nine o'clock in the morning of February 24, 1912, after the chimes of the Major Church, Juan Antonio Avilés, the cornet that served the orders of Agramonte, performed with the mambí clarion the touch of Attend Everyone, and then the Banda del Cuartel General de la República, under the direction of José Marín Varona, interpreted the chords of the National Anthem. Immediately, Amalia Simoni, widow of Major General Ignacio Agramonte y Loynaz, followed by her daughter Herminia Agramonte, pulled the rope that held the fabric of the National Ensign that kept the equestrian statue covered.

Throughout the 20th century, Agramonte Park became the scene of the most important cultural and political events in the city, highlighted by an environment of historical buildings in the public life of Camagüey.

In 2000, the Office of the Historian of the City carried out a rehabilitation process, with the aim of rescuing, highlighting and preserving the values that have identified the most central square, and the inauguration took place on February 2nd of the following year.

The Park was the scene in 2009 of the official proclamation of a part of the Historic Center of our city as Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

- Translated by Linet Acuña Quilez