CAMAGÜEY.— At the Luis Casas Romero Professional School of Arts, mornings begin with sounds unlike those of any other institution: scales repeated over and over, small fingers searching for precision on a keyboard, bows testing the right string, dance steps measuring time through the body. Within this universe, Mathematics seems to occupy a discreet place at first glance—yet it quietly sustains creation.

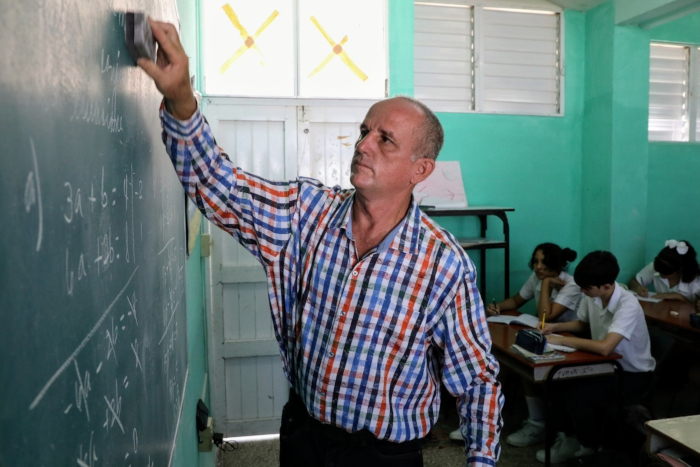

That is where Edilbert Pentón Carmenates can be found, a 55-year-old teacher. He was born in Remedios, the town where parrandas set the rhythm of the year, but since the 1980s his family has been rooted in Camagüey. He studied here, teaches here, and has devoted his life to helping adolescents understand that Mathematics is a key.

He arrives at school ready to turn numbers into music and movement. Because behind every scale there are proportions; within every arpeggio, patterns; in every counted step, a numerical sequence that gives structure to art. He is determined to make Mathematics an ally of artistic talent—so much so that his students consistently stand out in national competitions.

Listening to him took me back to my own classmates from academic contests: medalists who learned to love difficult problems, to celebrate discovery, to turn an idea over and over until it shone. In him, I recognized that same spirit.

—Did you choose Mathematics, or did it choose you?

—It was always my own decision. I liked it from childhood. I studied at the José Martí Higher Pedagogical Institute in Camagüey, graduated in 1993, and I’ve been teaching ever since—mostly at the junior high level. I worked in several schools in Najasa, Jimaguayú, and Camagüey, as well as at the provincial reference center, Ana Betancourt de Mora. I’ve been here since 2017.

—What is the challenge of teaching children who think with their bodies and their ears?

—It’s a pleasure. The key is bringing Mathematics closer through music and dance—helping students see it as a support for learning their profession. We use examples of figures who united both worlds. We start with Pythagoras, who devoted part of his life to music; in his schools, music was taught first because it liberated the soul. Fibonacci worked with sequences found in works of art like The Mona Lisa or Vitruvian Man. Dance is full of spatial and plane geometry. We use physical space—especially in ballet, dance, and folklore. One of the biggest challenges today in junior high is geometry, so Mathematics becomes a pillar of their artistic training.

—Have students ever found an “artistic” solution to a math problem?

—Of course. In dance class, I ask them to form a triangle with three aligned points, and immediately they say, “Teacher, that doesn’t make a triangle.” They discover it themselves—side lengths, angles, positions. That practical evidence stays in their memory far longer than an abstract lesson.

—Could you share another example of a creative problem you gave them?

—Sure. I once used the words butter, cheese, toast and asked them to choose the correct fourth option among milk, yogurt, cereal, and juice. The answer was yogurt, because of alphabetical order. The idea is to teach them to reason, not just to calculate.

—Does Camagüey’s cultural environment influence your approach to teaching and learning?

—I consider myself "Camagüeyano" (born in Camagüey), even though I was born in Villa Clara. I grew up between those two roots. I believe every professional—especially an educator—must love culture. To guide students, one must first learn how to learn and cultivate oneself constantly, especially now, in times of technology and artificial intelligence. Teachers must stay up to date in order to truly accompany their students.

“Once, during a class evaluation, I asked: What is culture? They started talking about music, dance… and I said, no—culture is everything. The word comes from cultivating thoughts, ideas, ways of behaving, everything.”

—If you had to choose one concept a musician should master, and one a dancer should deeply understand, what would they be—and why?

—For musicians, harmony: tuning, tones, and the structure of scales are directly linked to Mathematics. For dancers, the geometry of the body—how it moves through space, how it positions itself, how it uses angles and planes. Geometry doesn’t stay on paper; it becomes visible and tangible in their own bodies.

On the day of the interview, he told Adelante he had spent part of the early morning grading exams from 68 students competing at the municipal level. That discipline and daily dedication are what allow his students to achieve some of the highest scores in the country—even while maintaining intense artistic routines.

—Art education is often considered expensive. How does that investment translate into discipline and sensitivity?

—All education is costly. In the arts, beyond books and teachers, there are instruments, scores, rehearsal spaces, and libraries. But the reward lies in seeing children with aptitude and talent develop. When they learn Mathematics through their art, even if they don’t compete forever, they gain discipline, curiosity, and wisdom.

—How do you introduce academic rigor amid rehearsals, performances, and physical training?

—It starts with lesson planning. When I arrived, I asked myself: how do I make my students fall in love with Mathematics the same way they love their art? From that question, everything followed. At first, there was no competition work—everything revolved around the instrument. Gradually, we advanced. Last year, we achieved the highest Mathematics score in the country: an eighth-grade girl from this school.

“In ninth grade, there’s a level-promotion exam. We try not to interfere, but some students say, ‘Teacher, I’ll take the promotion exam—and still compete.’ For me, that’s another challenge: preparing them without stealing time from their specialty. We’re very strict—if a competition student struggles in their art, they don’t compete.”

Like him, there are still teachers who hold together the most fragile pieces: attention to talent, the Olympic dream, a love for rigor. Edilbert has advised on the design of the Mexican Mathematics Olympiad, yet his routine remains simple: he arrives by bicycle at the small school where students gather to practice. With no cutting-edge technology—only his method, his patience, and a piece of chalk—he trains them.

—You also prepare students from other schools. What is your strategy?

—It changes every year. I’ve spent 33 years in education and more than 20 preparing for competitions. Camagüey has been consistent in developing Mathematics contests. Over the past three or four years, we’ve achieved the highest scores in the country in eighth and ninth grade. Seventh grade is tougher—they start from zero. My strategy is five percent of me and ninety-five percent of the students. Primary education feeds us. We select students based on performance and work weekly, progressively.

“Right now, we prepare students at Enrique José Varona Junior High on Wednesdays from 8:00 to 10:30 a.m. This month, intensive training begins. Camagüey will take 31 students to the provincial contest. We have three WhatsApp groups—for seventh, eighth, and ninth grade—and some parents want to be included to know what we assign. Students solve problems and send them to me. Time is never enough.”

—Recently, several students won awards. That must be gratifying—you’re reaping what you sow.

—Mathematics competitions run all year long: local, national, and international events like the Iranian Olympiad and the May Olympiad. Recently, a wonderful idea emerged: the National Contest for Mathematical Culture, organized by the Cuban Society of Mathematics and Computing. Instead of solving problems, students showed—through artistic expressions—how they see Mathematics and Computer Science. My students were born with technology in their hands, so I insist they bring it into their minds. They competed with poems, songs, and short stories. Seventeen music students participated.

As if that weren’t enough, he also prepares future teachers at the Pedagogical School of Camagüey, working with a fourth-year group, and teaches Geometry to university students.

—What role does family play in your teaching work?

—A fundamental one. My family is small—I’m an only child. Without the support of my wife and my two children, none of this would be possible. Preparing for competitions and accompanying students takes an enormous amount of time beyond regular work hours. Sometimes grading exams at two in the morning is necessary, because the kids are eager to know their results.

—How do you imagine the future of the intersection between art and Mathematics in Cuban education?

—First, it has to be made visible. Everything must merge. I remember a professor in my first year of university telling me that a good teacher is always remembered. That idea has guided my teaching. I try to make my classes live up to it—to be remembered not as the person who taught addition or subtraction, but as someone who taught students how to think, how to organize ideas, and how to face challenges. That learning can be an exciting journey into the unknown.

Translated by Linet Acuña Quilez