CAMAGÜEY.— We began without electricity. Inside the Fénix Room of the Casablanca Multicine, a small generator barely powered a couple of cameras and lights—just enough to sustain a dream: a conversation with Teodoro and Santiago Ríos, the Canarian filmmakers who have learned to see Cuba as a homeland of childhood and memory.

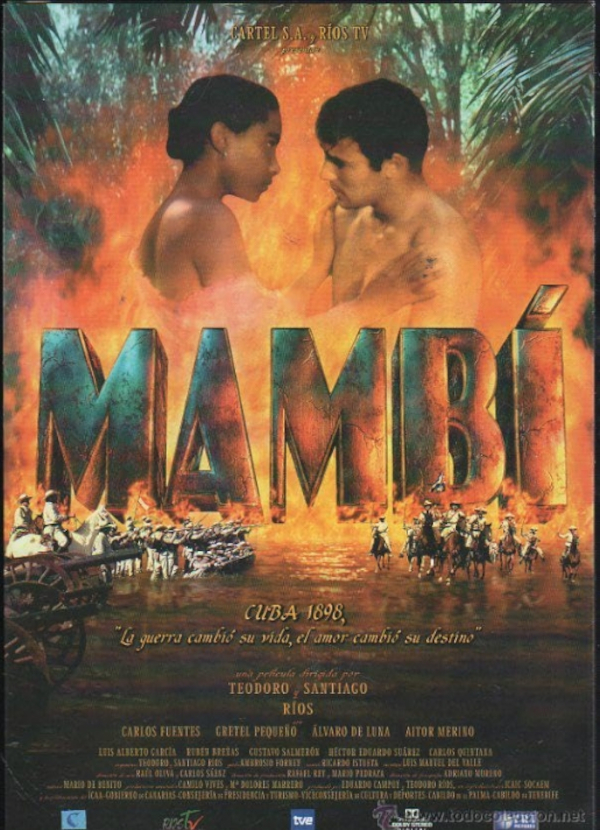

The exchange was part of El Almacén de la Imagen, which this year has had to relocate more than once. Its 35th edition has been postponed to December, when the film Mambí (1998) will be screened, but the conversation could not wait. There we were, with the minimum, with just enough—just as cinema is made in Cuba: with will and affection.

“They were supposed to connect from the César Manrique Educational Center in Tenerife, but it closed two hours early due to a rain alert issued by the Government of the Canary Islands. They improvised at the recording studio of a technician known as Kiko. From there, they recalled their ties with the island…”

Sometimes cinema begins like that—one lamp lit in the middle of a blackout. No electricity, yet full of light.

Gratitude goes to Benjamín Reyes and the Docurock Festival team for building this bridge between Tenerife and Camagüey; to Mi Camagüey Streaming and the Provincial Directorate of Culture for sustaining communication even in times of scarcity; and to everyone who made this meeting possible on November 12th.

Gratitude goes to Benjamín Reyes and the Docurock Festival team for building this bridge between Tenerife and Camagüey; to Mi Camagüey Streaming and the Provincial Directorate of Culture for sustaining communication even in times of scarcity; and to everyone who made this meeting possible on November 12th.

FAMILY MEMORY

Santiago and Teodoro Ríos greeted us with that blend of Canarian accent and Cuban memory that has always lived within them.

“We are always delighted to reconnect with our homeland in miniature. Even though we were born in Tenerife, we lived ten years of our childhood in Cuba, and, as they say, your childhood is your homeland,” said Teodoro.

They grew up in Havana and learned Cuban history. Their father created the celebrated 1951 portrait of Dulce María Loynaz; their uncle Santiago was a television and film actor in Cuba, at CMQ. “If you add that our father—from the island of La Palma—was born in Cabaiguán… well, Cuba has always been a part of us,” added Santiago.

FROM ISLEÑOS TO MAMBÍ

The idea for Mambí came, as often happens in cinema, out of an impossibility. “Isleños, about the founding of San Antonio, Texas, was meant to be our second film, but it wasn’t moving forward,” they recalled. Then another story emerged: that of Canary Islanders recruited to fight in Cuba’s war, some of whom ended up joining the independence cause.

“We wanted to rescue a story that connected the Canary Islands and the Americas,” said Santiago. “That became the basis of our trilogy. It wasn’t intentional, but it ended up being the Canary Islands’ film trilogy: Guarapo, Mambí, and El vuelo del guirre.”

Teodoro clarified: “It’s a very special relationship. In Cuba, we are isleños; everyone else is Spanish.”

A SCRIPT BETWEEN TWO SIDES

The film was also an act of balance, as it was co-produced with the Cuban Film Institute (ICAIC). “With the Spanish writers, the story leaned too Spanish; with Ambrosio Fornet, too Cuban,” they remembered. “We had to provide equilibrium.”

Mambí tells the story of Goyo, a young Canary Islander conscripted into the Spanish army who, upon arriving in Cuba, ends up deserting.

“The son of the landowner didn’t go to war,” Teodoro noted. “The poor did. Goyo had family in Cuba, and little by little, he gravitates toward the Cuban side.”

Santiago added: “We wanted an anti-war, human film. Not to idealize either side, but to show the disaster that any war is.”

A Cuban historian later told them: “You’ve cleaned up the Spaniards’ image.” They prefer to think they portrayed the human beings behind the factions.

CINEMA AS A BATTLEFIELD

Teodoro compared filmmaking to a train that departs full of dreams and gradually loses pieces along the way. “Cinema is very complicated—it’s like a war. You set off with illusions, knowing something will fail, and you must compensate with imagination. The perfect film doesn’t exist.”

Among their anecdotes, the most celebrated was their encounter with Andy García at the Los Angeles Latino Festival. “For being Cuban and having Cuban roots, I’ll give you half my fee,” he told them. “And how much is half?” “Nine million dollars.” “Well, thank you very much, Andy. We’ll call you.”

Everyone laughed. Because, like cinema itself, this story is sustained by humor and dignity.

BRIDGES TOWARD THE FUTURE

New ideas emerged from the Camagüey audience: Why not create more exchanges? “It seems like a wonderful idea,” Teodoro replied. “The connection is already in place with DocuRock.”

Santiago then spoke about what matters most to them when guiding new generations: “If time is good for anything, it’s for leaving a legacy. The magic word is perseverance. If ten years pass and you still believe in the project, keep going. One day it becomes reality.”

Teodoro highlighted a concrete possibility: the Canary Islands International Film Market (CIIF Market), where young Cuban filmmakers could pitch projects with an eye toward co-productions. Another bridge between islands.

A SUCCESSION IN MOTION

Today, the Ríos brothers are more connected to cultural work than to active production. Retired, they continue participating in talks, debates, and collaboration projects. The family production company, Festeam, is now run by Guillermo Ríos, Teodoro’s son, who directs the CIIF Market, a space that has grown over twenty-one editions to support independent cinema and connect international projects with European producers. The market awards prizes, allowing winners to attend events such as Cannes or Berlin, strengthening ties between emerging film industries and global circuits.

Meanwhile, Santiago has recently returned to filming with the short WC Story (Bathroom Story), produced by Cuban actor Joel Angelino, remembered for Strawberry and Chocolate. This sharp comedy set in a restroom was shot in an Art déco cinema on La Rampa in Havana—the very place the brothers visited as children—and will be screened this year at the Havana Festival of New Latin American Cinema, which is a return to their origins, both personal and cinematic.

A SPACE FOR CONNECTION

Amid daily challenges, these gatherings supported by the Asociación Hermanos Saíz and the Mi Camagüey Streaming team reaffirm something essential: that cinema, even without a lit screen, remains a place for encounter. Seeing the Ríos brothers converse with young Cuban filmmakers was more than revisiting a film from the past—it was creating continuity, proving that dreams, too, are inherited. In this bridge between Tenerife and Camagüey—supported by Benjamín Reyes through DocuRock and El Almacén de la Imagen—ties are strengthened that transcend islands and distance.

The light of the small generator that illuminated the Fénix Room became a precise metaphor: cinema, like life in Cuba, survives with whatever is available. And still it shines. Perhaps that is the deepest lesson Mambí leaves us: that there is always a moment when someone chooses to keep filming, keep believing, keep igniting the story from the darkness.

Translated by Linet Acuña Quilez