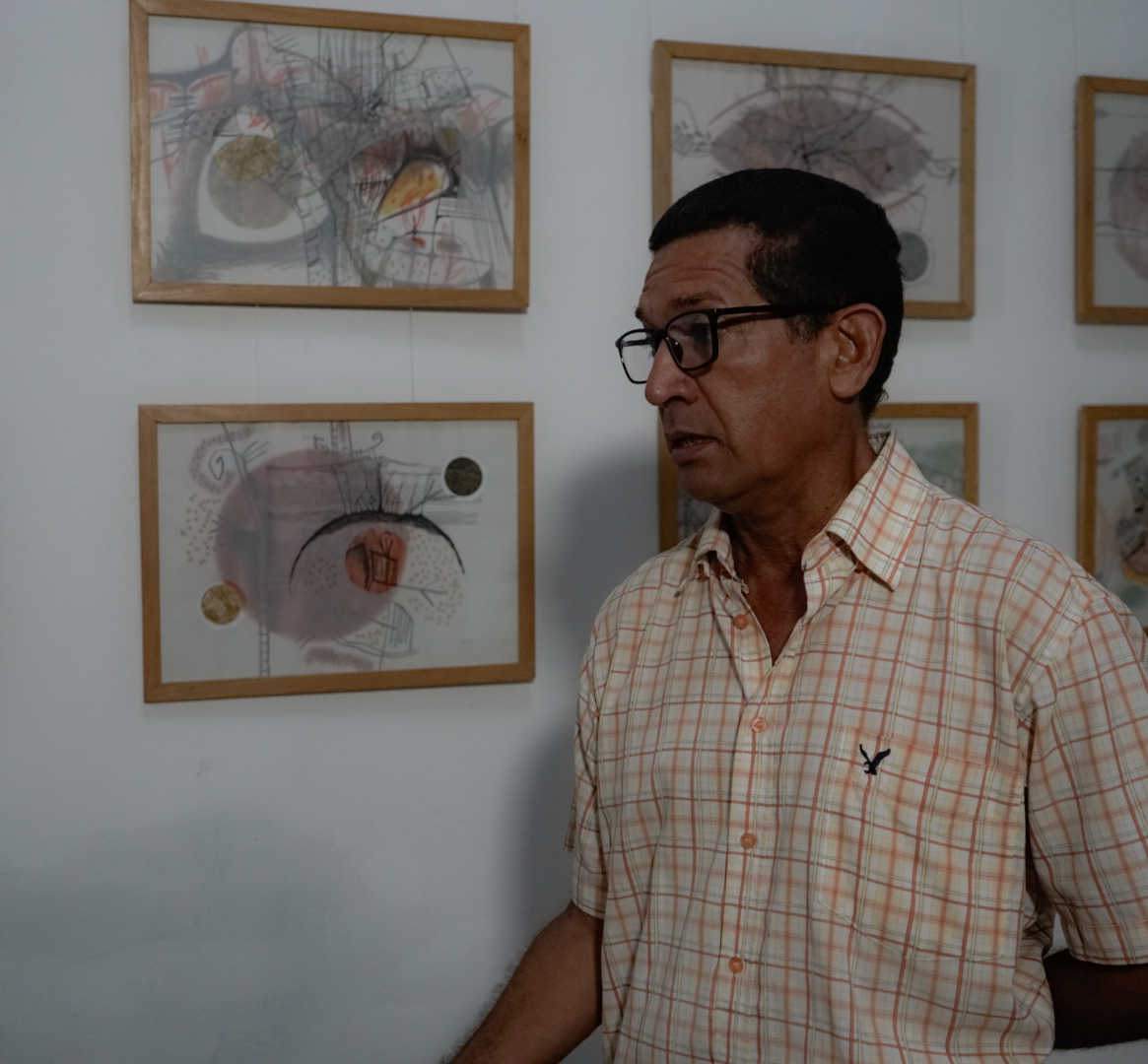

CAMAGÜEY — The aroma of freshly brewed coffee mingled with the morning freshness in the courtyard of the Alejo Carpentier Gallery. Between the white columns and wrought-iron tables, we spoke with Isnel Plana Pérez, painter and geologist, who was returning to a place that was once his own.

“I lived here for a while,” he confides. “I even bathed and slept here when I couldn’t get back to Sibanicú.”

That anecdote takes us back to the decade when he served as president of the Provincial Council of Visual Arts of Camagüey, before coordinating the Cultural Mission in Venezuela (October 2010 to September 2011). But that was not our topic. We came to talk about the Fidelio Ponce Salon Award he received in the curatorial project category for Butterfly Effect, an exhibition where science and art, past and future, the ancestral and the contemporary converge.

The trajectory of this man seems drawn with the same patience with which geology reveals its secrets: layers of experience, unexpected veins, and surprising turns. He trained as a geological engineer at the Higher Institute of Mining and Metallurgy of Moa, after beginning his studies at the Comenius University of Natural Sciences in Bratislava, Slovakia, where he delved not only into the mysteries of the Earth but also into the Slovak language, which he still preserves as a mark of that vital journey. He worked as a geologist from 1992, but his creative impulse led him to a second life: that of a self-taught artist, registered in the National Creators’ Registry.

Seen together, his works reveal a passage between the gestural and the geometric, the ephemeral and the enduring. In collage, he celebrates the fragility of the mended everyday; in acrylic painting, he affirms the monumentality of stone—as if alternating between recording the wound and seeking the sacred in matter. In both cases, his visual research transcends mere formal composition: it is a need to name the fracture and, at the same time, to touch the stone that survives.

In Butterfly Effect, Plana proposes a different kind of cartography: not one of precise coordinates, but of memory and spirit. His discourse flows between tradition and modernity, where nature ceases to be a resource and becomes an interlocutor. He speaks of Ana Mendieta, Leonardo da Vinci, Matisse, and Brancusi, artists who, like him, sensed that spiritual reservoir beating within the primitive, and still speak to us today.

His works, he says, are maps of consciousness: drawings and collages that do not seek to represent the world but to locate us within it, reminding us that the only possible coexistence is born from respect and communication with the Earth.

A CROSSROADS

The artist moves naturally between the scientific and the poetic. In Bratislava in the late 1980s, he learned to see “Europe’s grays,” the muted atmospheres he would later transfer to his art. Later, at the Higher Institute of Art (ISA) in Havana—although he attended for less than a year— he learned to organize his aesthetic thought. “ISA changed the way I see,” he says. “It forced me to be uncomfortable, to avoid doing what’s easy.”

Another figure emerges strongly in his story: painter Ileana Sánchez, whom he calls his “artistic mother.” He learned ceramics from her in secondary school, during his boarding years. “She still says I’m her son. She adopted me. She taught me rigor and discipline. I’m dying to go back to ceramics someday,” he confesses.

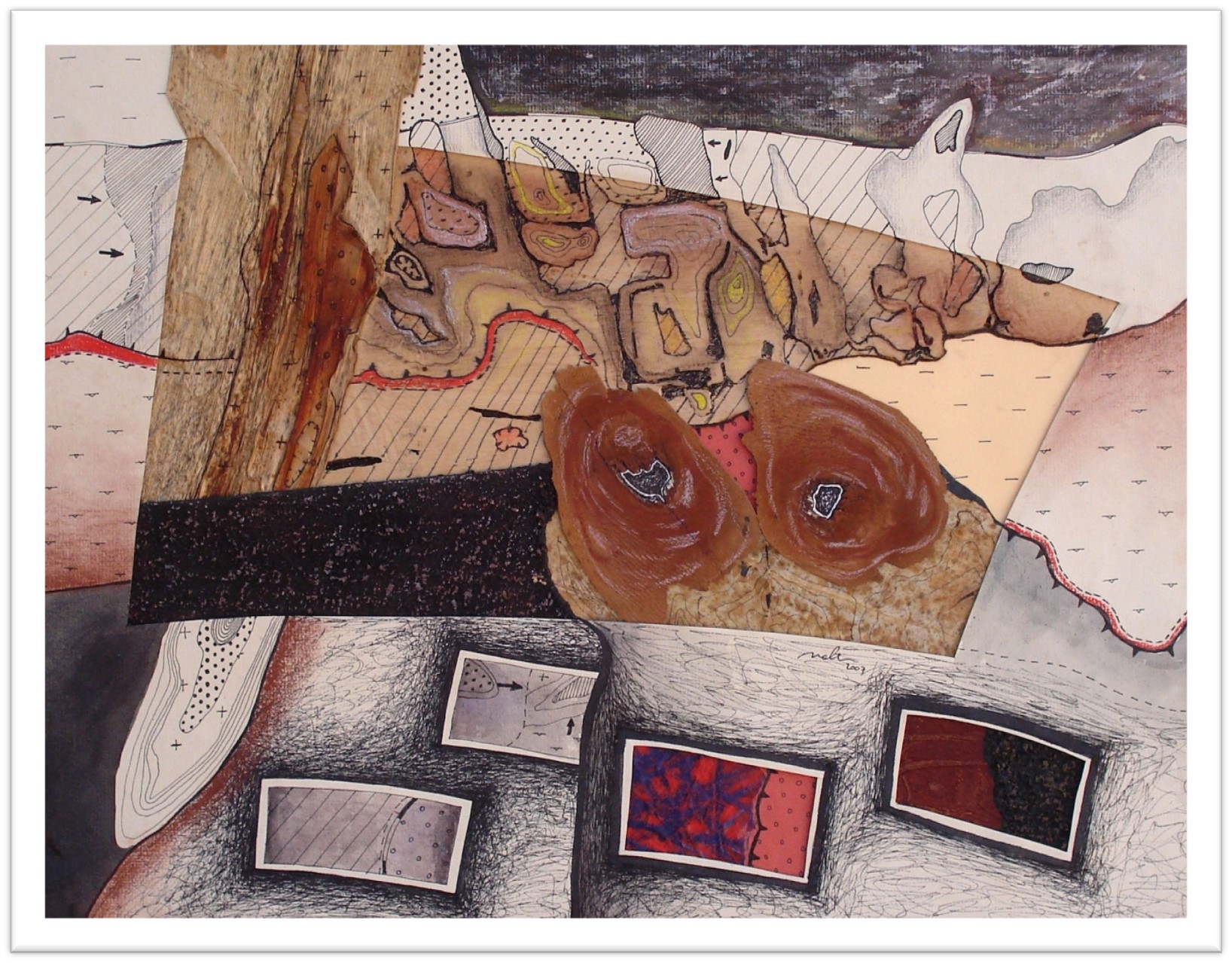

A quick look at his earlier works reveals a clear evolution—both technical and conceptual. In Poetry, Magic and Spring (1996), he shows meticulous drawing, full of organic details that evoke the natural world, with a distinct leaning toward the fantastic and symbolic. In Domestic Hangover (2004), his work gains chromatic force and expressiveness, integrating surrealist forms and freer composition, showing confidence in color and structure. Finally, in an untitled piece from the Geopretexts series (2007), one perceives an aesthetic maturity and consolidation of his personal style, where matter, texture, and visual metaphor fuse into a complex and deeply sensitive vision of the natural and human environment.

In his most recent phase, represented by Butterfly Effect, he takes a new leap by adopting the visual language of maps as both conceptual and aesthetic axes. The exhibition stems from a scientific idea that he transforms into visual philosophy.

“I appropriate the concept that an action in one place can have repercussions in another,” he explains. “I speak about how human knowledge generates effects—and how we often forget the essential: that the natural is usually more efficient than the artificial.”

In his Paliomundi series, he reworks ancient maps—even those by Leonardo da Vinci—intervening them with layers, translucent papers, natural fibers, and cracked earth textures.

“I want the viewer to see beauty,” he says. “Not to show the catastrophic, but to make people fall in love with the beauty of Nature.”

Plana maintains a dialogue between the precision of cartographic drawing and the creative freedom of art, but now his exploration is more abstract and poetic: the map becomes a metaphor for the invisible connections that link phenomena—just as the butterfly effect suggests. This phase reveals a mature synthesis of science and art, where technique refines and discourse becomes universal, inviting viewers to explore the hidden folds and resonances of both the inner and planetary landscapes.

DRAWING IN SIBANICÚ

One can imagine the calm Sibanicú sun falling over fruit-filled patios, where he has found his refuge. He wasn’t born there, but in Colombia municipality, when part of Las Tunas still belonged to Camagüey.

“The only thing that doesn’t make me feel like a stranger in Sibanicú is being close to the land,” he says.

For him, every work is also a map: “In art, I use what I learned as a scientist. Geologists spend their lives making diagrams, maps. That helped me keep drawing—to create my own textures and symbols.”

His worldview remains anchored to that root: the subsoil as explanation of wars, layers as metaphor for knowledge, the microscope as a window to abstraction. “In those layers there will always be lost knowledge—so that whoever comes next can keep searching,” he says, convinced that art, like geology, moves forward by digging.

From that perspective, he affirms that his works function as cartographies of cultural memory and ecological outcry. His scientific background also surfaces in reflections on climate change and how information is manipulated:

“Climate change is real. It’s not Nature that fails to adapt—it’s us. The Earth always finds a way to balance itself.”

As he speaks, memories of his geology student days resurface: his first box of Czech pencils, the color-coded maps, the fascination with quartz and agates. “When you find a mineral in nature, it’s already a perfect sculpture. There’s no way to improve what the Earth creates,” he smiles.

Today, he combines his creative work with his job at the Municipal Directorate of Culture in Sibanicú, where he supports programs and local artists. He says he has planned his work until age 60. He turns 57 this December. His next exhibition already has a title: Paragenesis, inspired by the microscopic vision of minerals.

GRATITUDE AND FUTURE

Our calm, thoughtful conversation unfolded between sips of coffee. Plana spoke of geological layers, maps, and textures—of how science dissolves into his visual art until it becomes visual poetry. In the nearby hall, one of his pieces seemed to await us: an expanded map, like an all-seeing eye, surrounded by circles containing the Earth’s memory—minerals, cracks, fossilized leaves, dust. There, his obsession was summarized: to look at the world as one who excavates.

As we said goodbye, Isnel listed his gratitudes—to the teachers who guided him, the colleagues who supported him, the neighbors who welcomed him.

“I left believing that what I did could have value because others believed in me. I owe a lot to many people.”

And so, with his feet on the Earth and his gaze on the maps of the future, Isnel Plana continues to draw an art that is also science, memory, and gratitude—an art that, like geological layers, quietly preserves the imprint of time, waiting for the next explorer bold enough to look.

Our interview has been a journey into the certainty that art can be as revealing as a cut through stone.

Translated by Linet Acuña Quilez