CAMAGUEY.- The universality of Martí, forged by the scope of his thoughts, places him as an indispensable foundation in the spiritual progress of our Homeland. This one-man-orchestra who was a poet, modernist, humanist, philosopher, journalist... is a recipe and reference manual for topics that will never go out of style, such as his vision of the fundamental cell in the flourishing of a nation: the worker.

If we investigate his epistolary we will find some evidence of his concern for that sector. In the context of the Chicago strike on May 1st, 1886, and the subsequent execution of the eight martyrs, on the fourth of that month, he told the director of the Liberal Party that "(...) It is not in the branch that the crime must be killed, but at the root. It is not in the anarchists that anarchism should be hanged, but in the unjust social inequality that produces them (...)”.

The impressions of El Maestro about the event also travelled to the newspaper La Nación, of Argentina. They were later published under the name of A Terrible Drama, and "(...) with a deeply reflective analysis scrutinizes the previous development of the labor movement in the powerful and unfair country, which tramples the humble native and immigrant (...)", says the historian, María Luisa García Moreno, in a writing for the Verde Olivo Magazine.

Within the accumulation of information and diversity of criteria that coexist in the digital space, orbits José Martí and the working class, a picturesque article by the Argentine professor at the University of Buenos Aires, Hernán Díaz. The author, without proof, declares that the Apostle "(...) unreservedly supported the execution, describing the victims with the rudest words, painting them as monsters and considering that the snake's head was being cut off with a single blow ( ...)”.

As a heretic's blasphemy, the "scholar" attempts to cover the Sun with one finger. He uses the classic modus operandi of tarnishing the image of the hero and, by transitivity, the Cuban Revolution as a student of Martí's wisdom. However, against fallacies and post-truths, there are immediate remedies such as José Martí, Guide and Companion, a book by diplomat Carlos Rafael Rodríguez.

He glimpses in the renowned politician the human quality and the link of the author of The Golden Age with the workers when he expresses that "he knew how to see the historical role of the working class (...)" and that these, in turn, were, "( ...) the force (...) that could support the development of the Revolution”.

As the "best among us" and the "ark of the alliance where the flag of freedom is kept," he described that population stratum as a hero, especially to find unity among the emigrants of Tampa and Key West. "The characteristic thing about José Martí is that he said that one had to knock on each of the doors (...) with the knocker that was capable of resonating," said Carlos Rafael.

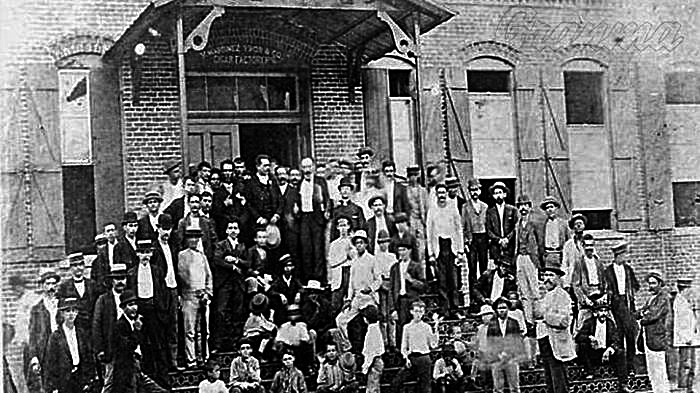

The previous words are complemented by those of the historian José Cantón Navarro, who refers in José Martí y los trabajadores that the composer of the Simple Verses "(...) is among the workers where he lives the longest, where he drafts and approves the resolutions that will constitute then the bases of the PRC, where that unique party of the revolution is organized, whose strength lies essentially in the workers (...)”. Although El Maestro's approaches to the working class are generally limited to the northern country, there are other precedents.

His stay in Mexico, between 1875 and 1877, gave him a holistic vision of the daily problems of the masses to earn their daily bread. During that period he worked as a correspondent for the Universal Magazine and, under the pseudonym Orestes, he wrote bulletins in which he accompanied the underprivileged with his pen, such as the one related to the claims of hat makers, who had been lowered cost of their productions.

"The strike (...), fair in all respects, places this branch of artisans in a distressing and difficult situation, deprived as they are of the daily sustenance that (...) they brought to their homes (...)", and in tune with that same tone and posture, the Apostle stands up in another publication in defense of the rights of the industrious indigenous people: "our workers rise up from a mass guided to a conscious class: they now know what they are, and their saving influence comes from themselves (... ) they were previously working instruments: now they are men who know and appreciate each other (...)”.

There are two recurring words in Martí's speech: fraternity and duty. Two words that he had also learned, in Spain, as the historian, María Caridad Pacheco González, recounts: "(...) according to the testimony of Pablo Iglesias, founder of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, he attended workers' meetings and was in the writing of advanced newspapers ( ...)”, also specifies that relations with the Mexican proletariat resulted so close that "when the first workers' congress in Mexico was held, in March 1876, they elected him a delegate (...)".

If we are talking about associations related to Martí, let us find out what the university professor, Hernán Díaz, thinks: “with whom José Martí should be related is not with Marx, but with whoever was his most important political influence, the Italian republican Giuseppe Mazzini (... )”, and the contradictory researcher continues: “(…) Like Martí, Mazzini was an enemy of class independence and worker strikes (...)”.

By inheritance and conviction, in the Greater Antilles there are plenty of boxers of the verb who know how to reply to the "connoisseur". From his corner, the deep voice of Carlos Rafael Rodríguez would resound like a hook to the chin: “When he said that the workers, due to their suffering situation, could perceive the truth better than others, he comes a little closer to certain conditions that are attributed to the proletariat (...) the conceptions have a certain link with Marxism, but they are not totally Marxist (...) This brings it closer to our positions, without identifying him with them (...)”.

The practice of the ideology and qualities of the National Hero, has been one of the maxims for the Cuban Workers’ Union, founded on January 28th, 1939. This date will be propitious for a double celebration, because the Apostle will also reach 170 years. From Lázaro Peña to the union leaders of the present, they have had on their shoulders the weight of "With everyone and for the good of all", and as a reference to a tireless man who, even after Dos Ríos, continues to work for the well-being of his people, without brushing the dust off the road.

- Translated by Linet Acuña Quilez